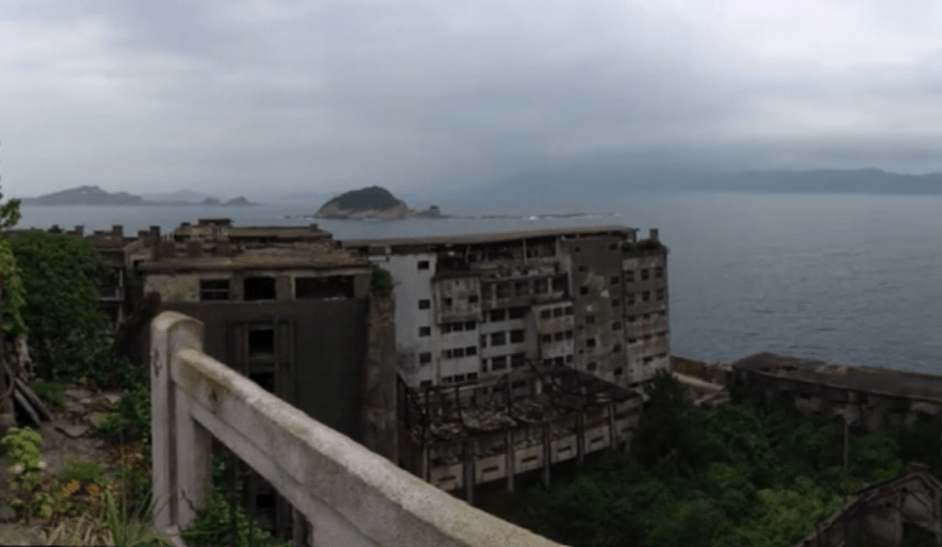

The island of Hashima is largely artificial, made from displaced materials and peoples. As coal-mining activities shifted in scale from centuries of family-organised excavations to a state-sponsored engine for industrial growth, so the 125 by 300 meter reef was metamorphosed. Sold to the shipping conglomerate Mitsubishi in 1890, a subterranean network of tunnels and chambers was carved out of the millenia of sedimented lithic layers. Waste from the mines was used to extend the site, which, by 1916, held Japan’s (then) largest concrete building as well as an encircling sea wall. It was amidst this dense environ that the conscripted labour of Japan’s Korean and Chinese colonial subjects took place between 1910 and 1945.

The mine disgorged coal for the salt-making industry, and emerging fleets of steam-powered ships. It also fed the production of cement for the construction of buildings, paths and tunnels. Slag was combined with limestones and shales and heated by a coal-fired kiln to produce clinkers; the ashes from the fires were also fed into the mix. Pulverised along with calcium sulfates, the resulting powder would ‘set’ when water was added but would then become impervious to the same so that cement could be used in marine environments in the form of sea walls, ships and so on. Into the cement would be poured hard-wearing aggregates such as pebbles and sand. During the manufacturing process, cement powder would also react with the slimy mucus of noses, throats and lungs, producing chemical burns and cancers. In order to augment the tensile strength of this newly-made rock, which was prone to crack rather than bend, steel rods were embedded in the mixture.

Even as it was being built, Hashima was becoming a ruin. As soon as it is made, the ‘integrity’ of concrete begins to break down at a micro as well as macro-level. Sulfates in acid rain weaken the cement binder, and salts from sea water crystallises in the pores of the concrete, fracturing its physical lattice. As the alkalinity of the cement is reduced, the electrochemical corrosion of the metal reinforcing supports is enhanced. Rusting flakes further destabilise the site’s structural integrity. Rooves and walls collapse into shattered shards that reveal their embedded pebbles and sands, and from which flourish bundles of steel wire like petrified sea anemones. Dripping with moisture from the humid air, the ground takes on the appearance of a newly accreting seashore.

Hashima became part of a highly controversial, 2015 designated UNESCO World Heritage Site labelled “Sites of Japan’s Meiji Industrial Revolution: Iron and Steel, Shipbuilding and Coal Mining, Japan’ in large part because of its concrete transformations.According to the UNESCO World Heritage Committee, “The rapid industrialization that Japan achieved from the middle of the 19th century to the early 20th century was founded on iron and steel, shipbuilding and coal mining, particularly to meet defence needs” (World Heritage Committee, 2015). An industrialisation, South Korea was quick to point out, built on the displacement of people who became forced labourers.

Hashima became the focus of a 2013 collaborative project funded by the AHRC called The Future of Ruins: Reclaiming Abandonment and Toxicity on Hashima Island, involving myself, Carl Lavery (Performance, University of Glasgow), Carina Fearnley (STS, UCL), Mark Pendleton (East Asian Studies, Sheffield University), Lee Hassall (Fine Arts, University of Worcester) and Brian Burke-Gaffney (Cultural History, Nagasaki Institute of Applied Science). Since 2013, a series of performances, talks and papers have emerged, including:

Project Report on The Future of Ruins.

Map 3: Sea Wall. Fearnley and Dixon.

Lavery, Carl, Deborah P. Dixon, and Lee Hassall (2014) The future of ruins: the baroque melancholy of Hashima, Environment and Planning A 46.11: 2569-2584.

Dixon, Deborah P., Mark Pendleton, and Carina Fearnley (2016) Engaging Hashima: Memory Work, Site-Based Affects, and the Possibilities of Interruption, GeoHumanities 2.1: 167-187.

Lavery, C., Dixon, D., Hassall, L., Pendleton, M. and Fearnley, C. (2016) Return to Battleship Island. In: Shaw, D. B. and Humm, M. (eds.) Radical Space: Exploring Politics and Practice. Series: Radical cultural studies. Rowman and Littlefield: Lanham. Pp. 87-108.

Dixon, Deborah (2019) From becoming-geology to geology-becoming: Hashima as geopolitics. In: Bobette, a. and Donovan, A. (eds.) Political Geology. Palgrave Macmillan, Cham. Pp. 147-165.

Hashima Island. Photo by Deborah Dixon

Exposed Steel. Photo by Carina Fearnley.

Hashima from the Sea. Photo by Carina Fearnley.

Looking Out from Hashima. Photo by Carina Fearnley.

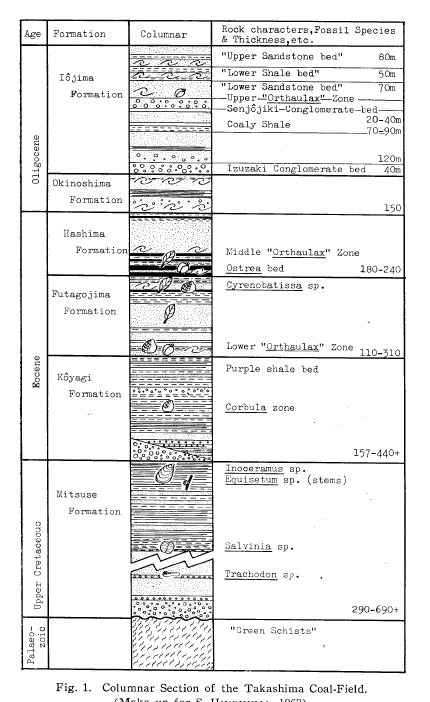

Columnar Cross-Section. From Matsuo, H. (1967). A CRETACEOUS SALVINIA FROM THE HASHIMA IS.(GUNKAN-JIMA), OUTSIDE OF THE NAGASAKI HARBOUR, WEST KYUSHU, JAPAN, Transactions and proceedings of the Paleontological Society of Japan. New series. Vol. 1967. No. 66. PALAEONTOLOGICAL SOCIETY OF JAPAN.

Geological Cross-Section of the Hashima Coal Mine. From Yamamoto, E. et al (1967) Geological Exploration of Mitsuse and Hashima Off-Shore Area in the Takashima Coal Field, Mining Geology 17.84: 200-213.